1. The Setup: When History Hit Back

The archive room was always cold, but that night the chill felt personal.

Rows of metal shelves towered over me, filled with gray boxes and yellowing folders—century‑old paper that still carried the ghosts of ink and sweat and war. The hum of the scanner, the soft click of the mouse, the glow of the monitor: it should have been a normal late shift.

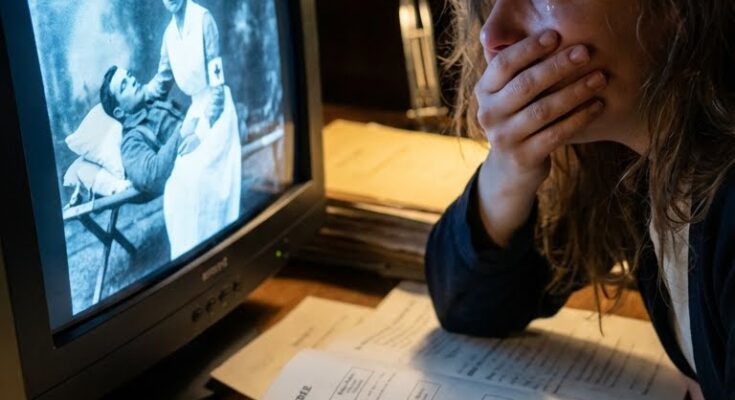

Instead, I was staring at a 1917 hospital photograph that had just set my entire family history on fire.

On the screen, the photo was clearer than any book reproduction I’d ever seen. High‑resolution. Every crease in the nurse’s uniform, every strand of hair escaping her cap, every shadow under the soldier’s eyes.

She was holding him like the world was collapsing. One arm behind his shoulders, one hand pressed against his chest, her fingers curled into the bloody fabric of his uniform. His head rested against her shoulder, eyes half‑closed, mouth slightly open like he was trying to say something he’d never get to finish.

I’d scanned the original glass plate from a box labeled “Unidentified WWI Field Hospital – Belgium.” No names, no metadata, just a date and a location scrawled on the envelope.

Normally, that would have been the end of it. Scan, tag, upload. Another sad image among millions.

But tonight, my supervisor had asked me to test an experimental facial recognition algorithm on some of our oldest collections, just to see whether it could match faces from pre‑digital centuries to our modern user database.

I’d chosen the hospital photo at random.

The algorithm analyzed the nurse’s face first. Green squares blinked around her eyes, nose, mouth. A loading bar crawled across the bottom of the screen. Then the results appeared:

MATCH CONFIDENCE: 97.8%

Name: Elise Laurent

Born: 1893, Vosges, France

Died: 1968, Lyon, France

The system linked to a digitized death certificate and a grainy ID photo from the 1950s. Same sharp jawline. Same intense eyes.

Then the soldier:

MATCH CONFIDENCE: 96.9%

Name: Adrien Laurent

Born: 1891, Vosges, France

Died: 1917, Ypres, Belgium

A military record. A casualty list. No photo—until now.

The last line of the match panel made my stomach drop:

Possible relationship to user: 3rd great‑grandfather and 3rd great‑grand-aunt (via DNA and tree match).

My username was highlighted next to it.

I thought it was a bug. A weird coincidence. Some kind of false positive.

Then I clicked into the underlying record set that the algorithm had used to cross‑verify the match, and saw a scanned ledger from a French military hospital in Belgium.

At the top of the page: June 1917. Ypres.

Halfway down, two names written in the same cramped, hurried handwriting:

Laurent, Adrien – age 26 – shrapnel wounds – status: critical

Laurent, Elise – age 24 – nurse – newly assigned

Next to their names, in the “Notes” column, someone had squeezed in smaller text, almost as an afterthought:

“Les deux se sont reconnus comme étant frère et sœur, séparés dans l’enfance. Le soldat est décédé dans ses bras quelques heures plus tard. Aucun des deux n’avait su pour l’autre avant aujourd’hui.”

The system had auto‑translated it, but I didn’t need it. I grew up hearing French murmured over holidays, secrets slipped between generations.

“The two recognized each other as brother and sister, separated in childhood. The soldier died in her arms a few hours later. Neither had known about the other before today.”

I pushed my chair back so fast it hit the filing cabinet behind me. My heart was pounding in my ears. I looked from the ledger to the photo, back to the ledger.

Brother and sister. The nurse and the dying soldier. Holding each other in a war hospital, not knowing they were family until that very day—in the last hours of his life.

And they were mine.

Not distant, irrelevant names in a history book. My blood. My father’s ancestors, the ones we could never trace past “orphans from the war,” the ones my grandmother refused to talk about.

For a moment, the archive room felt like it was spinning. The air thickened. I felt like I was intruding on a moment I had no right to see.

Then the researcher in me kicked in.

If this was true, someone in my family had known this story once. Someone had written those words. Someone had chosen to let it disappear.

I downloaded the photo and the ledger entry, printed them with shaking hands, and shoved them into a folder.

There was only one person still alive who might have answers.

My grandmother, Anne.

The woman who had always shut down when the conversation turned to the war. The one who’d told us her father was “no one important” and that some stories were better left alone.

2. The Backstory: A Family Built on Silence

To understand why that photo cut so deep, you have to understand the way my family treated the past.

On paper, we were the perfect modern French‑American success story. My father, Jacques, had emigrated from France to the U.S. in the 1980s, married my American mother, and built a comfortable middle‑class life in the Midwest. We had family dinners, bilingual Christmas carols, and framed black‑and‑white photos of “the old country” in the hallway.

But ask any question that went deeper than the 1940s, and you hit a wall.

“Your great‑grandfather died in the war,” my grandmother would say, her lips tightening. “That’s all.”

“Which war?” I asked once, when I was twelve.

She glared at me over her glasses. “In Europe, ma chérie, there is always another war. It doesn’t matter which one.”

As a kid, you learn where the landmines are. War was one of them. The other was her childhood.

“We had a hard time after,” was all she’d say. “You should be grateful you don’t know what hunger feels like.”

My father tried to fill in the gaps when he could.

“Your grandmother’s father was an orphan,” he told me when I was fifteen, washing dishes after dinner. “He grew up in a home run by nuns. She doesn’t like to talk about it because it reminds her of shame—poverty, charity. In her mind, that’s failure.”

“Do we know anything about his parents?” I asked.

He shook his head. “Only that he was ‘a child of the war.’ That’s what the nuns wrote in his file. No names, no photos.”

So when a high school friend introduced me to genealogy websites, I dove in.

I built trees, pulled records, learned to read 19th‑century French cursive. I traced my mother’s side back to stubborn New England farmers in the 1700s, my father’s mother’s side back to a line of Vosges lumberjacks and textile workers.

My grandmother rolled her eyes. “Digging in graves,” she called it. “Looking for ghosts.”

Her father—my great‑grandfather—was a void. Born 1925, “foundling” on the birth record, raised in an orphanage. No parents listed. No birth address. Just a line where a father’s name should have been, and a dashed line where the mother’s name might have gone.

“Sometimes the past wants to stay buried,” my grandmother said when I showed her the file. “Listen when it tells you.”

But I’d built a career—and now a life—on refusing to do that.

By 2024, I was working for a European genealogy company, one of those sleek platforms with TV ads about “discovering who you really are.” My job was to find the stories in the data, to stitch together lives from records, photos, and DNA matches. I spent my days helping strangers find their great‑grandparents.

I never expected to find mine staring back at me from a World War I deathbed.

3. The Climax: Confronting the Keeper of Secrets

By the time I reached my father’s house with the folder, the sun was low and the winter light had turned everything a washed‑out gray.

He opened the door, frowning. “You didn’t call. Is everything okay?”

“No,” I said, my voice thinner than I wanted it to be. “I need to show you something.”

At the kitchen table, I laid out the photo and the printed translation of the ledger note.

He stared at the image for a long time. He was a quiet man by nature, but this silence was different. Heavy. Charged.

“You recognize her, don’t you?” I asked softly.

He flinched, just slightly. “She looks like my mother,” he admitted. “The nose, the eyes. When your grandmother was young, before—” He cut himself off.

I tapped the names on the printout. “Elise and Adrien Laurent. Brother and sister. Separated in childhood. Reunited by chance in a field hospital. He died in her arms without knowing she existed until that same day.”

He read the note, lips moving silently. When he looked up, his eyes were wet.

“And they’re ours?” he asked. “You’re sure?”

“DNA doesn’t lie,” I said. “The system matched both of them to me, and through me to you. Elise is our 3rd great‑grand‑aunt. Adrien is our 3rd great‑grandfather. Their blood goes straight to Grandma. She’s the one who comes from the orphan.”

He sat back, staring at the photo like it might start moving.

“My mother always said her father was ‘a child of the war,’” he murmured. “She never said which war. I assumed she meant the Second, with the Germans. But 1925… it makes more sense that he was born after the first.”

“If Adrien died in 1917,” I said, “and Elise lived until 1968… someone had to raise a child born around 1925. Someone had to decide he was better off as a ‘foundling’ than as the son of a nurse who’d already lost a brother.”

He knew where I was going. He didn’t like it.

“My mother wouldn’t have lied to me,” he said, too quickly. “She kept things from me because they hurt. That’s not the same as lying.”

I slid another document across the table. A photocopy of a letter I’d found attached to Elise’s death record.

It was dated 1967, written in neat, shaky handwriting to a Catholic orphanage in the Vosges region. Signed: “Sœur Laurent (formerly Elise Laurent).”

In it, she asked for news of “the boy born in 1925, my nephew by blood, whom I relinquished to your care at the insistence of my superiors.” She wrote about losing her brother in the war, about being pressured to join a religious order, about “the shame of an illegitimate child in a small village.”

The orphanage had stamped the letter as received. No reply was attached.

At the bottom, someone had scribbled in red pencil: “Child adopted by the Dubois family, 1932. New name: Pierre Dubois. Records sealed.”

“Dubois,” my father whispered. “My grandfather’s name. Pierre Dubois.”

He stared at the letter, then at the photo, then at me.

“All this time,” he said slowly, “my mother knew she was the granddaughter of a war nurse and a dead soldier. Instead she told us her father was ‘no one.’ A nothing. A child from nowhere.”

And then, like a veil lifting, I saw it in his face: anger.

Not the mild frustration of a son whose mother was “difficult,” but the deep, generational rage of someone realizing his entire identity had been edited for him without consent.

“She erased them,” he said. “She erased their names because she was ashamed. She turned our great‑grandfather into an abstract tragedy instead of a real man whose sister watched him die.”

He picked up his phone with shaking hands.

“Who are you calling?” I asked, though I already knew.

He hit the speaker button. The phone rang twice.

“Oui?” my grandmother’s voice crackled through, old and sharp as ever.

“Maman,” my father said, switching unconsciously to French. “I need to ask you something about your father.”

Silence.

Then, warily: “Why now, Jacques? After all these years, why now?”

“Because we found him,” he said. “We found his parents. We found them in a photograph. And we found the sister who gave him up and then tried to get him back.”

There was a soft sound on the other end. Not quite a gasp. More like someone flinching when a knife goes exactly where they feared it would.

“You went digging in graves,” she said, her voice turning to ice. “I told you not to.”

“And I’m done living in the dark because you don’t like the light,” he shot back. “We deserve to know where we come from.”

I placed the photo in front of the phone, even though she couldn’t see it. My heart was pounding. This was the breaking point—the moment you’d normally cut to commercial.

“Mamie,” I said quietly, switching to the gentle French I’d used as a child. “In 1917, a nurse named Elise held a dying soldier named Adrien in her arms. They recognized each other as brother and sister, separated as children. He died that same day. She later gave up a baby boy in 1925, and that boy became Pierre Dubois.”

Silence stretched.

“The ledger says they were siblings,” I continued. “The DNA says they’re ours. And a letter from 1967 says Elise tried to find the boy she gave away.”

I swallowed.

“That boy was your father, wasn’t he?”

What she said next detonated everything.

“You think this is a romantic tragedy,” my grandmother said quietly. “But you have no idea what I did to keep you all safe.”

4. The Resolution: Revenge, Truth, and a Different Inheritance

My grandmother didn’t hang up.

She could have. It would have been easier. Instead, she did something she’d refused to do for eighty‑five years: she told the truth.

Bit by reluctant bit, through pauses and sighs and the occasional curse, a family story unraveled—a story that had been wrapped in shame and silence for three generations.

Her father, Pierre, had grown up hearing he was a “charity child.” The nuns told him his mother had been a “fallen woman” who died in the war. They never mentioned an aunt. They certainly never mentioned a soldier brother who’d died in her arms.

When Pierre was seven, a couple adopted him. Good Catholics, strict but not cruel. They gave him the Dubois name and a little piece of normality. But the town never forgot where he came from. “Orphan.” “Bâtard.” Words kids hurled in playgrounds like stones.

“He never knew how to be proud of himself,” my grandmother said, her voice cracking. “How could he, when the church called him sin made flesh?”

In the 1950s, when my grandmother was a teenager, a woman in a nun’s habit came to their village. Old, tired, eyes haunted. She asked to speak to Pierre.

“She’s your aunt,” my grandmother’s mother said afterward, shaking. “She thinks she can just walk back in here and claim him after leaving him to rot in an orphanage. Over my dead body.”

My grandmother watched through a crack in the door as her father confronted the nun—Elise.

“You gave me up like garbage,” he told her. “You let them tell me I was a mistake. You waited twenty‑five years to decide you care. I don’t want your pity. I don’t want your God. I don’t want you.”

He threw her letter into the stove.

“She never used the name Laurent again after that,” my grandmother said softly. “Whatever she did in the war, whatever she lost—he refused to forgive her. And I grew up watching him drown in that bitterness.”

Years later, when my grandmother married and had children of her own, she made a decision.

“I cut them off,” she said. “The soldiers, the nuns, the orphans. All of it. I decided my children would not grow up as ‘bastards of war.’ So I told you your grandfather was just… no one. Better a blank than a stain.”

“That wasn’t your call to make,” my father said, his voice hoarse. “You stole our choice.”

“I stole your shame,” she snapped. “And no one ever thanked me.”

“But you also stole our pride,” I said quietly. “Adrien died a hero. Elise held her brother while he died. She saved other men. She tried, however clumsily, to fix what she’d done. That’s not just shame. That’s courage and regret and humanity.”

There was a long pause.

“I didn’t want you romanticizing pain,” my grandmother said finally. “Turning it into some pretty story.”

“It’s not pretty,” I said. “It’s messy. It’s ugly. But it’s ours. And your revenge on their memory—erasing them—only hurt the people who came after.”

The word hung in the air: revenge.

Because that’s what it was, in the end. Her father’s revenge on Elise for giving him up. Her revenge on history for branding him a mistake. Her revenge on the past, paid for with our ignorance.

“I’m not asking you to forgive them,” I said. “I’m asking you to let us know them.”

Silence again. Then a sound I’d never heard from my grandmother before: a small, broken sob.

“I kept that habit in a box,” she whispered. “The one she wore when she came to the village. I told myself I kept it as a warning. Really, I kept it because I couldn’t throw her away a second time.”

She cleared her throat.

“There’s a box in my closet,” she said. “Old letters. The habit. Some photos I stole from the orphanage file before they burned the records in the ’60s. If you want your ghosts, come get them. But don’t come crying to me when they haunt you.”

Then she hung up.

My father and I stared at the phone.

“What do we do now?” he asked.

I was shaking. I didn’t know whether to scream or laugh. But what I did next shocked everyone.

I put my hand over his and squeezed.

“We stop letting dead people dictate how we live,” I said. “We go to her house. We take the box. And we put their names back where they belong.”

We drove to my grandmother’s that same night.

She didn’t come to the door. She’d left it unlocked. A shoebox sat on the hallway table, old and battered, with “DO NOT OPEN” scrawled across the lid.

Inside were letters from Elise to the orphanage, never answered. A faded photograph of her in her nurse’s uniform, younger than in the hospital picture. A scrap of a newspaper clipped in 1925 about a “hero of the 1917 offensive” named Laurent, survived by “a sister in religious service.”

And at the bottom, carefully folded: a nun’s habit, patched and worn, that smelled faintly of old wool and incense.

My father lifted it to his face and sobbed.

We scanned every document. We built a new branch on the family tree. We attached Elise and Adrien’s names to the photograph in our company’s archive, replacing “Unknown nurse, unknown soldier” with “Elise and Adrien Laurent, siblings reunited at the Ypres field hospital, June 1917.”

We wrote their story in both French and English. We attached the hospital ledger, the letter, the orphanage note. We removed the word “foundling” from my great‑grandfather’s profile and replaced it with “son of Adrien Laurent and an unknown mother; raised by the Dubois family.”

We gave them back to history.

And then, because the internet loves a goosebump story, we wrote a version for the company blog. We told the world about the 1917 photograph that, in 2024, revealed a brother and sister who’d been separated as children and reunited only in death.

The post went viral. People shared it with captions like “I’m crying at my desk” and “history is wilder than fiction.” Strangers commented that they saw their own grandparents in those faces, that they wished they knew their own hidden stories.

My grandmother called two weeks later.

“I saw your article,” she said. No greeting. No small talk. “You made them saints.”

“I made them human,” I said. “Which is more than anyone ever allowed them to be.”

There was a long exhale.

“I kept that photo on my bedside table,” she admitted. “The one from your article. The one with Elise in the hospital. I thought I’d hate it. Instead… I talk to her.”

I smiled, even though she couldn’t see it. “What do you say?”

“That she was a coward,” my grandmother said. “And that I was, too. And that I’m tired.”

We didn’t fix everything. Decades of shame and silence don’t dissolve in a single conversation or a viral post. But something shifted.

At Easter, my grandmother came to dinner for the first time in years. She brought a small, framed copy of the 1917 photo and set it on the sideboard.

“Family,” she said simply, when my younger cousins asked who it was.

Now, when visitors ask about the picture, my father doesn’t shrug and say, “Oh, just some anonymous war photo.” He tells them:

“That’s my great‑grandfather, Adrien, dying in his sister’s arms. They never knew each other until that day, because people decided shame was more important than truth. My daughter found them in a database a hundred years later.”

Sometimes, he adds, “We spent a century being angry at the wrong people.”

If there’s any revenge in this story, it’s not against Elise or Adrien.

It’s against the idea that silence protects us better than truth does.

Our revenge is that we broke the pattern. That we chose to inherit their names and courage, not just their trauma. That a photograph meant to document anonymous suffering now carries two real identities—and a family that refuses to forget them again.

A 1917 military hospital photo shows a nurse holding a dying soldier.

In 2024, facial recognition revealed they were brother and sister who’d been separated as children and never knew.

And in 2025, their descendants finally did what no one had allowed them to do in life: stand side by side, in the open, as family.